Published on

Tuesday, November 19 2019

Authors :

John Mayes and John Auers

For a number of reasons, we thought the early 70’s tune “Right Place, Wrong Time” by the idiosyncratic singer/songwriter Dr. John (real name – Malcolm John Rebennack Jr.), was an appropriate and timely tie-in to today’s blog. From a superficial standpoint, we both share our names with the good “Doctor,” who also would have celebrated his 78th birthday tomorrow if he hadn’t passed away earlier this year. More importantly, though the title line aptly describes our discussion about how crude supply developments have led to challenges for refiners who invested billions in heavy crude capabilities over the last two decades, only to see the heavy crude discounts on which those investments were justified, narrow significantly. This narrowing has resulted from several developments, which have both increased supplies of light crude and decreased heavy crude production. On the light crude side, the Light Tight Oil (LTO) boom certainly came as a surprise, as a decade ago light crude production was expected to continue on a long-term declining trajectory. Conversely, heavier and sour barrels, from prolific deposits in Latin America and the Middle East, which were supposed to be the crude supply of the future, has seen production declines, primarily due to “above ground” limitations (Venezuelan malaise, lack of investment in other parts of Latin America, Canadian pipeline delays, OPEC quotas, etc.; however, help could be on the way, which could eventually reward the refiners who made the investments necessary to effectively process heavy sour crudes (delayed cokers, hydrotreating, sulfur capacity, etc.). In the short term, the 2020 IMO low sulfur bunker regulations should give a noticeable “bump” to the heavy crude discount as significant volumes of high sulfur resid (which have to find new homes) will make their way into the deep conversion refinery feedstock pools. Over the longer term, while we expect the “above ground” production issues will be resolved and light crude production growth will slow, both the timing and magnitude of these developments is highly uncertain. We’ll discuss all of this today, as we ponder when the “right time” for heavy crude refiners returns.

“Would have been the right move, but I made it at the wrong time”

In the past, U.S. refiners have proven willing to spend tens of billions of dollars to upgrade their refineries to keep pace with changing crude qualities, and if the timing is right rewards can result in handsome payouts for those projects; however, sometimes unanticipated developments in the oil patch lead to project returns which do not always achieve their hoped-for potential. This has happened many times in the past (for example, investments in the 1960’s and 70’s to run Middle East crudes, only to be met by successive oil embargos). More recently, U.S. Gulf Coast refiners invested tens of billions of dollars in coking additions and expansions as heavy crude production from Latin America (Venezuela, Mexico, Ecuador, etc.) was ramping up beginning in the 1980’s and 90’s. This process continued after 2000 with the growth of Canadian bitumen-based grades which stimulated coking additions in PADDs II and IV, and was initially met with success as production growth kept the new capacity well supplied with inexpensive crude.

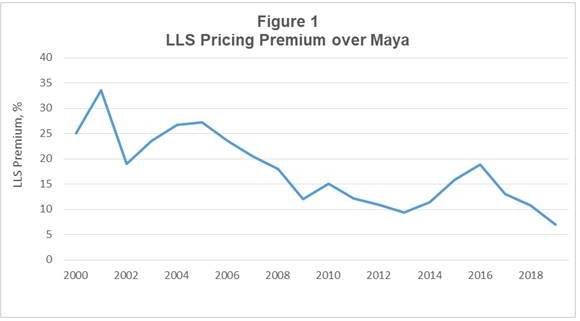

The economics of coking operations depend on a sufficient spread between light and heavy crude prices, which we define as the spread between the marker USGC light crude (LLS at St. James) and the marker heavy crude (Maya FOB Mexico). An LLS price more than 20% higher than the Maya price is generally sufficient to justify the construction of new coking units. A differential at this level will not only recoup operating costs but will also provide a reasonable return on the construction capital costs. An LLS premium of 10-20% will only cover operating costs but will not likely stimulate new construction. When the LLS premium over Maya falls below 10% however, refiners often reduce coker operating rates as coking economics become marginal.

The highly volatile LLS premium over Maya averaged over 25% in 2000-2005 (Figure 1) with spikes above 30%, leading to very healthy coker economics; however, since 2005, this differential has slowly eroded due to the supply developments we noted earlier. This decline has ramped up recently, falling to average only 7% in 2019 through October, largely due to the precipitous drop in Venezuelan production along with loss of OPEC’s heavier barrels and Canadian crude curtailment. At these levels, many cokers are operating in the “red.”

Markets generally act rationally to what is expected, but what is expected does not always occur. A good way to highlight this is to compare what the markets thought would happen five years ago with what has actually occurred.

“Refried confusion is making itself clear” – We all got it wrong

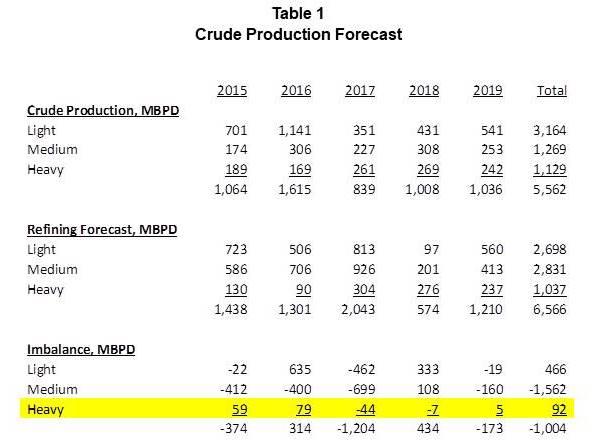

In 2015, Turner, Mason & Company (TM&C) collaborated with Schlumberger Business Consulting in the preparation of a global crude oil production forecast. This study evaluated production on a field basis and assessed not only the volumes of crudes likely to be produced but also the qualities as well. Crudes were aggregated into five grades, from heavy (below 24 °API) to condensate (above 45 °API). We show this data into Table 1 which has been condensed into three grades of light, medium, and heavy.

In 2015, it was calculated that heavy crude production would rise by approximately 1.1 million BPD in the next five years while output of light and medium grades would rise by 3.2 million BPD and 1.3 million BPD respectively. TM&C also prepares a global biannual refinery construction outlook. This study in 2015 concluded that slightly over 1.0 million BPD of new refinery additions which would process heavy crudes would be added through 2019. The highlighted row in Table 1 compares the difference in these two forecasts which, for heavy crudes, is exceptionally low. In other words, the global refining industry was very much in sync with what was expected by the global crude production industry for heavy grades. There is a greater variance in the lighter grades due to the ability to switch between grades.

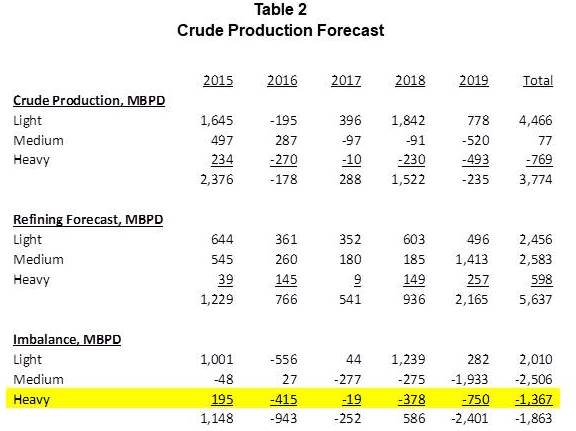

Actual results however, have not met the expectations of 2015. Table 2 shows the actual production of crude grades since 2015 and the actual refining additions. Instead of rising by 1.1 million BPD, heavy crude production declined by nearly 800 MBPD in the last five years. Conversely, light crude output jumped by nearly 4.5 million BPD instead of the forecast increase of 3.2 million BPD. Production of medium grades was essentially flat. Partially offsetting the reduction in heavy production, actual heavy crude refining additions were also lower by over 400 MBPD. Instead of the balanced estimate, this situation created a net imbalance between heavy crude production and refining construction by 1.4 million BPD for the 2015 through 2019 period.

Both the over-production of the light grades and the under-production of the heavy grades have contributed to the decline in the light/heavy crude differential since 2005. Most of these productions shifts however, have occurred in five countries: the U.S., Mexico, Russia, Venezuela and Iran.

While the shale revolution in the U.S. was already well developed in 2015, the global crude price collapse beginning in mid-2014 kept future growth expectations in check. As a result, the actual surge in U.S. output in 2018 and 2019 was not anticipated. In the last two years, output from the U.S. rose by nearly three million BPD with the increase almost exclusively in the light grades. These increases resulted in U.S. light crude oil production in 2019 being higher than the 2015 estimates by 2.6 million BPD and accounting for all of the global light increase.

Adding to the light crude surge was an increase in Russian production. Dominated by Urals, a light sour grade, output from Russia rose by 750 MBPD in the last five years. Offsetting the Russian increase, however, was a decrease in light production from Iran. While the previous economic sanctions against Iran were not formally rescinded until January 2016, the markets in 2015 were generally presuming a settlement was near and expecting an increase in Iranian output. Output did rise from 3.3 million BPD in 2014 to peak in 2017 at 4.5 million BPD. With the new sanctions, production in 2019 is estimated at 3.1 million BPD which is 1.1 million BPD below the 2015 forecast.

Economic sanctions have also contributed to the decline in heavy production from Venezuela, although the biggest factor has been a near total collapse in the economy of that country due to mismanagement and the pull out of foreign investment. Since 2014, Venezuelan production has fallen from 2.6 million BPD to below 800 MBPD currently. Most of this decrease is in the heavy grades. Mexico has also lost heavy production. Total output from Mexico has fallen by over 700 MBPD between 2014 and 2019 with nearly 60% being Maya. While most of the 2019 shortfall in heavy production is related to Mexico and Venezuela, OPEC quotas (which have disproportionately lowered heavier grades) and government mandated curtailments in Western Canada have also had an important impact.

“Wonder which way I go to get on out of here” – Supply trends may be changing

Contrary to recent trends, it is likely that the global production of heavy crude grades will increase while future growth in light U.S. grades will become more subdued. Output in Venezuela can only decline slightly more and the potential of growth (due to the massive resource base in the next decade) is probable (although the timing is very uncertain and dependent on a return of stability and foreign investment). There are also numerous other heavy growth opportunities in Canada, Brazil, other parts of Latin America, Iraq, Iran, the Neutral Zone, and the North Sea. All is not rosy for heavy crude production growth potential however, as policies to reverse energy industry reform in Mexico by the Obrador government could lead to declining heavy crude production in that key country.

On the light side of the spectrum, robust outlooks of continued U.S. LTO growth have been tempered lately, with the result that most forecasts have more modest projections for the future. The prospect of more aggressive heavy growth and more modest light growth would indicate a widening of the future light/heavy crude differential. This topic is under further review at TM&C and will be one of the Special Topics discussed in the next edition of the Crude and Refined Products Outlook, which is scheduled to be issued in February 2020. In addition to analyzing the aspects of the current market, we will also be presenting a forecast of the future light/heavy differential and a discussion as to the shifting market conditions supporting this forecast, including the potentially substantial impacts of IMO 2020. For more information on this report or any of our other analyses or our consulting capabilities, please send us an email or give us a call at 214-754-0898.