Published on

Tuesday, April 7 2020

Authors :

John Auers and Robert Auers

Last week, we discussed the challenges refiners are experiencing in the face of the sharpest and quickest drop in demand the world has ever experienced. Our focus in that blog was on how much refinery utilization would have to decline, the difficulties associated with “turndown” limits on units and the problems caused by the uneven declines across different product groups. In our blog from two weeks ago, the subject was the significant shift in crude differentials being experienced in the market due to both the COVID demand impacts and the Saudi/Russia “oil war” and how those would impact refiners. In today’s blog, we continue along these lines to address which crudes refiners are likely to back out of their plants as they reduce runs and the factors that will determine those decisions, with our focus being on the U.S. refining industry. In discussing this subject, we will first lay out the fundamental factors which influence the types of crudes refiners purchase and the regional differences influencing those factors. We will also take a look at how those crude slates looked going into the current crisis. Using this information, we will then discuss which crudes are most likely to cause refiners to channel Dee Snider/Twisted Sister and tell their crude suppliers, “We’re Not Gonna Take It.” In today’s blog, we focus on the inland sections of the U.S. (PADD’s 2 and 4), where the crude slate changes are a bit more straightforward, following up next week with the coastal regions (PADD’s 1, 3 and 5), where refiners have more complex decisions to make.

Factors Determining Crude Slate Decisions

Refinery crude buying decisions are logically premised on building the most economical crude slate for the refinery – this means producing the optimal combination of the highest value product slate with the lowest cost crude slate. There are sometimes exceptions to this rule in the case of refineries owned by major foreign crude oil producers (Motiva, for example) or long-term supply arrangement that may prevent refiners from adjusting quickly to changing crude and product supply and demand environments. Further, the most economic crude for a refinery may not always be the cheapest. For example, a light sweet crude refiner may choose to buy West African (WAF) crude at a premium to other grades due to the fact that WAF crude typically has very high middle distillate yields and therefore produces a higher value product slate. In addition, most refineries have operational constraints that limit crude purchasing decisions. They include limits to bottoms and/or light ends handling, TAN limits, sulfur limits, solids limits, and a variety of other potential processing or handling constraints.

With that in mind, U.S. refiners have shifted crude buying patterns tremendously over the past 20 years. These shifts have primarily been driven by three major production trends – growing western Canadian production beginning in the late 1990s, growth of U.S. light tight oil production beginning in 2007 (but really accelerating in 2011), and declining Latin American heavy crude production beginning in the mid-2000s and accelerating with the rapid decline in Venezuelan production over the last few years. Other developments have also had major regional impacts on crude purchasing decision as well, such as declining Californian and Alaskan production, declining North Sea production, and growing Russian, Brazilian, Iraqi and, at times, West African production.

PADDs 2 & 4 – History

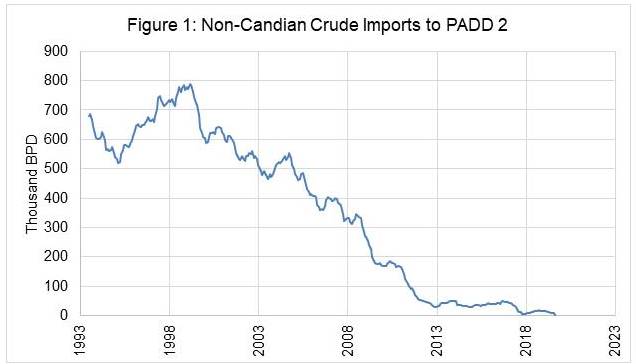

PADDs 2 refiners originally processed primarily locally produced and Canadian crude, but as inland crude production began to shrink in the mid-1980s, regional refiners were forced to process increasing volumes of imported crude oil, which was shipped north (primarily on Capline) from the U.S. Gulf Coast (USGC). This placed PADD 2 refiners in direct and disadvantaged competition with USGC refiners who could buy the crude at lower cost and ship products to the Midwest via pipelines like Explorer and Teppco. However, as Canadian production growth accelerated in the late 90s, many Midwest refiners began replacing imported and Gulf of Mexico crude with Canadian barrels. As the new Canadian growth was essentially all heavy (with the exception of synthetic crudes), a strong economic incentive emerged for inland refiners to increase their capability to process heavier crude slates. This led to a slew of heavy crude upgrade projects across PADD 2, including at Whiting (BP), Lima (Husky), Toledo (BP/Husky), Detroit (Marathon), and Wood River (P66/Cenovus). Then, with the emergence of the Bakken tight oil play in 2007 (with growth accelerating in 2010/2011), essentially all non-Canadian imports were replaced with inland North American crudes. Figure 1 shows this decline in non-Canadian crude imports to PADD 2.

This shift has provided a major benefit to inland refiners. Due to the inland demand for foreign crude imports, which had to be piped in from the U.S. Gulf Coast, PADD 2 refiners were forced to pay a premium for their crude prior to the surge in Canadian and domestic production. This can be seen in the Brent – WTI (Cushing) differential, with WTI priced at an average premium of about $1.50/Bbl vs. Brent prior to 2007. In 2007, this dynamic started to reverse, and by 2010 Brent began to consistently trade at a premium to WTI. This “flip” in the Brent-WTI differential was the result of growing inland crude production (primarily in the Bakken), which exceeded the capacity of PADD 2 and 4 refineries to handle these growing volumes, forcing the incremental barrel to move to either PADDs 1 or 3. A similar trend could be observed with heavy crude pricing, where continued growth in Western Canadian production overwhelmed inland refiners ability to process it, forcing the incremental Canadian barrel to the USGC. As a result, PADD 2 refiners are able to purchase heavy Canadian crude at a discount to their coastal peers. Over time, the continued growth in both U.S. and Canadian crude production has led to continued new pipeline completions from the Mid-Continent to the USGC, including the Seaway reversal/expansion, Keystone Marketlink, DAPL/ETCOP, and the Capline reversal coming in 2021. As production growth has exceeded available pipeline capacity, differentials have, at times, blown out and provided exceptional pricing advantages to inland refiners. Even in times of sufficient capacity, inland refiners continue to experience crude price discounts in line with spot pipeline tariffs to the USGC.

Looking Forward

In the current environment, with production and demand set to decline dramatically in the near term in both U.S. and Canada, inland refiners will be more challenged. From the week ending March 20 to the week ending March 27, PADD 2 refinery utilization decreased from 88% to 81% – and we expect this number to fall farther in the coming weeks, certainly below 70% and possibly bottoming out below 60% (or even approaching 50%). The drop in PADD IV utilization has been even more pronounced, with utilization there coming in at just 75% for the week ending March 27 and with prospects for further declines into the 50’s likely as well, at least until the COVID-19 lockdowns remain in place. In the near term, the most important factor driving low margins and refinery utilization in PADDs 2 and 4 is the lack of local demand and limited ability to access other refined products markets. Moreover, many inland refiners face competition from the USGC, as pipelines such as Explorer and Teppco provide an outlet for them to access inland markets. While we expect regional pricing differentials to keep flows on these pipelines low, their mere existence will further cap margins for inland refiners during the COVID-19 lockdowns, as USGC refiners would be incentivized to begin shipping on these pipelines if they could justify it economically. Further, given the inability of inland U.S. refiners to access foreign crudes with the reversal of Capline underway right now (and the lack of an economic incentive to do so even if they could), inland refiners are unlikely to make significant changes to their crude slates in the current environment. Refiners will adjust to optimize yields, maximizing diesel and minimizing jet and gasoline yields at lower throughput rates and this may incentivize refiners to alter their crude slates somewhat. However, due to their limited availability to access crude beyond domestic and Canadian grades, the shift in regional crude slates will not be significant.

Longer-term, once the COVID-related lockdowns are eased, crude prices will likely remain low for some time due to the need to work off inventories, the residual economic fallout from the lockdowns, and the potential for continued OPEC-Russia overproduction. It remains unclear how these issues will play out, but we will know more about the latter one after the emergency OPEC++ meeting set to be held this week. We are also seeing early signs that COVID-19 infections are plateauing in many “hot spots.” Despite these hopeful signs, we still expect much lower crude prices in the back-half of this year and into next year than we had predicted in the last edition of our Crude and Refined Products Outlook (C&RPO), which we issued in February before the extent of the COVID crisis was known. Canadian production will likely return rapidly when demand returns as production shut-ins are unwound and medium-term declines are unlikely as natural decline rates in the oil sands are very low, but growth is likely to slow considerably as low prices lead to lower capital spending.

In the U.S., light tight oil production is likely to fall for some time, with a bottoming in U.S. production likely not seen until late 2021 in our view. As this happens, it will pressure inland crude differentials, particularly if production levels fall below minimum volume commitments on takeaway pipes, limiting the crude price advantages that many inland refiners have been able to take advantage of over the past several years. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that inland refiners will be forced to pay a premium for crude as production will not be expected to fall to a level such that incremental light crude barrels will no longer need to move to the USGC. As a result, the crudes slates of inland refiners are unlikely to change significantly once the COVID-related lockdowns end, but the crude price advantages that they’ve enjoyed over the past 10+ years may be subdued, at least until U.S. tight oil production rebounds in 2022 and 2023.

In this rapidly changing and very uncertain environment, Turner, Mason & Company will be following developments related both to the COVID-19 pandemic and responses and OPEC+ actions very closely. We will be analyzing how those developments impact crude prices, differentials, product demand, crude production, refinery utilizations and ultimately industry margins and prospects. Some high-level aspects of these analyses will continue to be presented and discussed in this blog over the next few weeks and months. We will be incorporating the analysis in a detailed and comprehensive way in the next edition of our C&RPO, scheduled to be issued in the summer. As always, the C&RPO will include a detailed forecast of both crude and refined product prices, product demand, refinery capacity changes, and a variety of other key industry parameters. For more details about this publication or other TM&C services, please visit our website or give us a call.