Published on

Thursday, October 31 2024

Authors :

Harold "Skip" York - Senior Vice President and Chief Energy Strategist

“No. Mr. Bond, I expect you to die”

Auric Goldfinger in Goldfinger

On October 16, 2024, Phillips 66 announced plans to cease operations at its Los Angeles-area refinery (P66-LA) in the fourth quarter of 2025. The company will work with the state of California to supply fuel markets and meet ongoing consumer demand. This blog discusses how losing another fuels refinery could impact the gasoline supply-demand balance for California and what risks it might raise for market and price stability.

Basis for decision

The Phillips 66 refinery in Wilmington, California has a capacity of 139 mbd, which makes it the seventh largest refinery and accounting for about 8 percent of the state’s refining capacity. The refinery produces about 80 mbd of gasoline and about 50 mbd of diesel and jet fuel.

Phillips 66 is not leaving the West Coast. They still will have their newly minted renewable diesel plant (50 mbd) in Rodeo, California, in addition to the petroleum fuels refinery (100 mbd) in Ferndale, Washington.

So why shrink their West Coast portfolio? The company cited the asset’s low profitability relative to other assets in the company’s portfolio. There also is growing uncertainty of market dynamics based on demand profiles and regulatory burden. These uncertainties make it difficult to plan for the life of an asset and allocate capital. They also impact the competitiveness of California assets for capital relative to other assets in a company’s portfolio.

This is about more than just a refinery

P66-LA employs about 900 employees and contractors. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, average refinery operations and maintenance jobs in California pay about $91,000. When including overtime, their take-home pay can increase to over $150,000. By contrast other hourly skilled labor jobs in California pay about $49,000. Many of the workers at P66-LA could face the dilemma of accepting a job for almost half of what they currently make (assuming they can find one) or join the migration of over 500,000 fellow Californians since 2020 and leave the state for opportunities elsewhere.

California has been a challenging market for some time

In 2000 California had 19 fuels refineries and by the time P66-LA closes in 2025 the state will have no more than 8. Most of the early closures were small refineries that could not afford the capital fixed costs required for compliance with new environmental regulations (both state and federal).

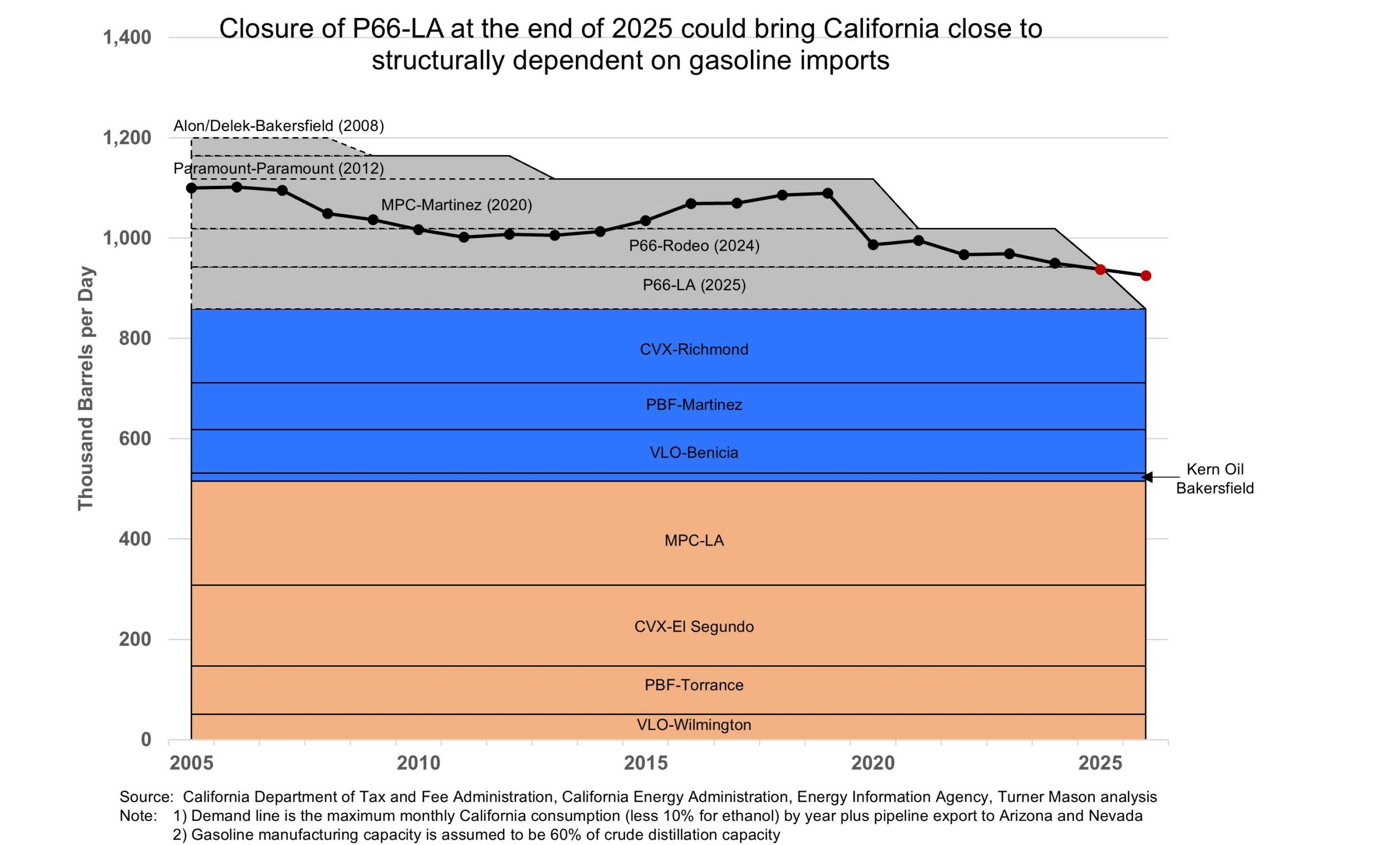

Using CEC (California Energy Commission) Transportation Fuel Assessment data that was published earlier this year (https://www.energy.ca.gov/publications/2024/transportation-fuels-assessment-policy-options-reliable-supply-affordable-and), we created a simple graphic to illustrate how refinery closures and gasoline demand have evolved.

According to California Department of Tax and Fee Administration data, gasoline demand peaked in 2018 and declined at an annual rate of 2.7% since then. The demand line in the chart reflects the monthly maximum consumption (less 10% to account for ethanol) plus gasoline pipeline movements to Arizona and Neveda for each year. We extend the line to 2026 (represented by the red dots) by assuming California’s gasoline demand continues to decline at 2.7% p.a. and out of state pipeline movements remain constant.

The horizontal bars reflect the gasoline production capacity of each refinery based on a simple assumption that 60% of a refinery’s crude distillation capacity can be converted to gasoline. The grey bars reflect refineries that already have closed or repurposed and we add P66-LA to this stack. The blue refineries are in northern California and the tan refineries are in southern California.

If P66-LA did not close, then by 2026 California would run a slight gasoline surplus of about 80 mbd (10% of demand) when no refineries are in maintenance or without unplanned outages. However, the closure of P66-LA moves the market into a structural gasoline deficit meaning the state will become dependent on constantly importing volumes of gasoline from as far away as Asia or Europe.

Declining demand is not the only pressure on California refineries to remain viable. There are several forthcoming regulations that are creating uncertainties for refiners both in terms of acquiring crude oil and fulfilling product demand. The combination of these uncertainties exacerbates challenges in their decision-making. And there are more uncertainties to come with the gasoline margin cap, revisions to LCFS and Cap-and-Trade, and the newly signed Assembly Bill X2-1 on minimum product inventory requirements. During the legislative hearings TM&C attended, advocates of this bill could not really explain how mandating supply to be held in inventory until the state deems it be released into the market would mitigate price volatility during unpredictable periods following events, such as, geopolitical (e.g., Middle East conflict that led to crude oil price spikes) or unplanned refinery outages (inside or outside California).

California’s fuel specification exacerbates its isolation risk

The state is often referred to as a “fuel island” because it is geographically isolated from other U.S. refining centers in the Gulf Coast and Midwest. In addition, California has made policy choices that further isolates itself from other petroleum markets. CARB gasoline has much different fuel specifications than the reformulated gasoline sold in other parts of the U.S. However, the difference in these specifications is based on EPA tailpipe emission tests from over 30 years ago.

Making gasoline to specification is a blending routine. It’s not that refineries in other markets lack specific processing equipment to make CARB gasoline. The bottleneck is that most lack the experience and the segregated tankage necessary to blend batches to the tight specifications. Those capabilities are found in California (and Washington) because those refiners make this boutique fuel as part of their regular operations.

As California moves to a structural gasoline deficit, the supply chain of necessary gasoline blend stocks would stretch all the way to Asia or Europe. The sailing time is at least 30 days and the longer the supply chain the greater the risk of disruptions (e.g., weather, ship mechanical issues, refinery outages, geopolitical events).

The likelihood of higher and more volatile product prices increases as the deficit window widens. Product vessels are smaller (with higher unit costs) than crude oil tankers. The smaller product vessels also mean an increase in harbor traffic with the resulting congestion increasing demurrage costs. This geographic risk is exacerbated by California isolating itself by choosing to have a gasoline grade that is not fungible with other reformulated gasolines in surrounding markets.

California is at risk of additional refinery closures

In June 2024, TM&C completed a Transportation Energy Supply Chain Infrastructure and Investment Study (TESCII) on the state of California. We analyzed the stability of the existing road liquid transportation fuel supply chain and risks to its viability in the future. The key insights from our analysis include: (1) California crude oil production is in sharp (15% p.a.) decline, (2) crude oil pipelines are approaching closure risk due to minimum volumes, (3) growing marine movements may eventually reach limits, and (4) policymakers should look at the cumulative impacts of several policy rather than treating each in a vacuum.

In the study, we surmised that it was not a question of “if”, but “when” refiners could be forced into difficult decisions such as the one Phillips 66 made on October 16.

A link to the Executive Summary of our study can be found here.