Published on

Thursday, January 26 2023

Authors :

Harold "Skip" York

The challenge of balancing refinery yields with evolving product demand.

In the movie, “The Rock”, John Mason (Sean Connery) might have had U.S. refiners in mind when he said, “Well, Womack, you’re between The Rock and a hard case.” Refinery product yields and product demand are constantly in a state of flux, but balancing yields with demand looks to be increasingly more challenging. By understanding causes and solutions of the imbalance, refiners can better assess options for repositioning their assets to improve competitiveness. Thus, strategies need to include both adjusting yields of existing processes and investing in new technologies to match the expected product demand profile of the future.

The share of petroleum gasoline (relative to diesel and jet) in U.S. transportation fuel demand has been declining since the 1980s. Part of this trend was driven by refinery gasoline production adjusting to ethanol, increasing its share of retail demand from less than 1% (2002) to 10% (2012). We believe this trend continues and possibly accelerates as penetration of EVs in the vehicle fleet becomes material. Thus, EV penetration is the second cycle of reduced petroleum gasoline demand with which refiners are having to contend.

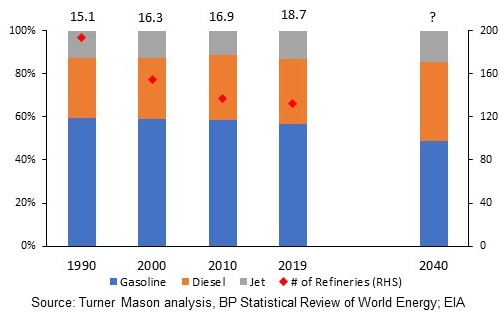

As Figure 1 below shows, one of the implications of the historical trend was the closure of smaller and more gasoline dependent refineries despite total refining capacity peaking at 18.7 MMBPD in 2019 (2023 is 0.7 MMBPD below 2019). Surviving assets made selective investments to leverage economies of scale and operational flexibility to maintain competitiveness.

Figure 1: U.S. Liquid Transportation Fuel Demand Share and Refinery Capacity

Over the last decade, challenges of declining U.S. petroleum gasoline demand have been exacerbated by a lighter crude slate resulting from the surge in shale crude oil production. The EIA reports the average crude gravity at U.S. refineries was 30.5 º API in 2010 and jumped to 33.0º API in 2022. The resulting increase in refinery gasoline production required an increase in exports of almost 1.0 MMBPD since 2010 to balance supply with US demand.

Refineries also made operational adjustments to shift product yield from gasoline towards diesel and jet. Much larger yield shifts require capital projects, such as hydrocrackers or investing in renewable fuels production. These sorts of projects take years to design and complete and must be accompanied by a conviction they would keep the refinery competitive for long enough to earn a return on the committed capital.

The U.S. refining system was designed to produce gasoline with yields typically 50% or more of the total product slate. If demand for gasoline continues to decline and demand for distillates increases as a percentage of total product demand, refining companies will need to assess their options including possibly rationalizing their systems and individual facilities to contend with this rebalancing. Refiners with access to waterborne logistics will have the optionality to export more gasoline, but land-locked facilities will need to look harder at re-optimizing feedstocks and process configurations. If gasoline supply falls faster than the drop in demand due to the way the U.S. system rebalances, this could result in tight markets, higher fuel prices, price volatility, and supply shortages because of the mismatch.