Published on

Tuesday, April 21 2020

Authors :

John Auers and Robert Auers

Over the last two weeks, we have discussed how the unprecedented drop off in petroleum demand from COVID-19 lockdown measures is impacting crude slates at U.S. refineries. In the previous blogs, we looked at both the inland regions (PADDs 2 and 4) and the largest refining region, PADD 3. Refiners in all three of these regions have benefitted (tremendously at times) from the light tight oil (LTO) boom due to their ability to access the growing volumes from the various basins in Texas, Oklahoma, North Dakota and the Rocky Mountains. They have also profited similarly from increasing production from Western Canada. Most PADD 3 refiners are also able to leverage their location on the coast to bring in waterborne crudes when economics are favorable. In today’s blog, we look at the other two coastal regions (PADDs 1 and 5), which also have access to those waterborne barrels, but unlike the other regions, don’t have pipeline access to domestically produced LTO and very limited access to the Western Canadian crudes. These regions also have product market challenges even in normal times, and the massive demand “cliff” from the COVID-19 mitigation measures is forcing refiners on both the East and West Coast to have to make difficult decisions in regards to reducing crude runs or even shutting down their plants entirely. Recently, Marathon was the first refiner to announce that they would shut down a plant (their 166 MBPD refinery in Martinez, California) in either of the two regions and although no U.S. refiners have done so yet on the East Coast, North Atlantic Refining (NARL) earlier decided to bring down their 130 MBPD Come-by-Chance refinery in Eastern Canada. Both refineries are expected to come back on line once demand returns, but, depending on how long the current situation persists, it is possible that one or more additional shutdowns could yet occur in these regions. In today’s blog, we will review the PADDs 1 and 5 crude supply and demand environment and how the declines in crude throughputs necessary to balance the markets in those regions are impacting crude slate decisions.

PADD 1

As noted above, both PADDs 1 and 5 have multiple disadvantages when it comes to crude supply compared to the other PADDs. First, neither region is connected by pipeline to the booming LTO production basins, and the Jones Act makes the marine transport of these domestic crudes from the USGC to PADDs 1 and 5 uneconomic. Both PADDs also have negative dynamics regarding In-region production, with PADD 1 only having nominal levels and with California and Alaska volumes in long-term decline. In addition, PADD 1, aside from the United refinery in Warren, PA, has no pipeline access to Canadian crude and PADD 5 has only limited access via the Transmountain Puget Sound spur to the Washington state refineries. As a result, refineries in these regions are forced to rely primarily on waterborne imported crude, expensive railed volumes coming primarily from North Dakota and smaller volumes of heavy crude railed from Canada (with the decreasing Alaska and California barrels still an important base load in PADD 5).

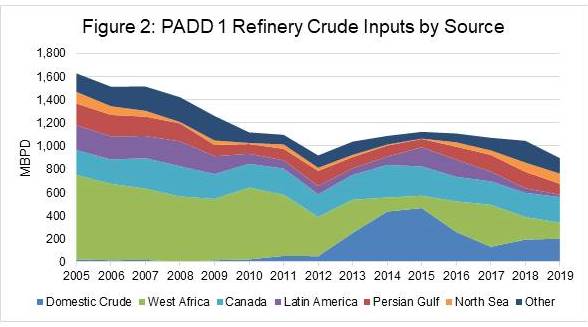

Due to challenging economics resulting from high crude acquisition costs and falling regional product demand, several major PADD 1 refineries have shuttered over the past fifteen years. The most notable of these closures have been Philadelphia Energy Solutions (330 MBPD), Eagle Point (145 MBPD), Marcus Hook (178 MBPD), Yorktown (70 MBPD), and Port Reading (70 MBPD of VGO/resid capacity). As a result, PADD 1 refinery crude inputs have fallen from over 1.6 MMBPD in 2005 to less than 900 MBPD in 2019 and below 800 MBPD since the PES refinery closure in June 2019. Due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, these levels have now fallen to about 450 MBPD (per EIA data for the week ending April 10) and are likely to go even lower as the COVID-19 lockdowns persist.

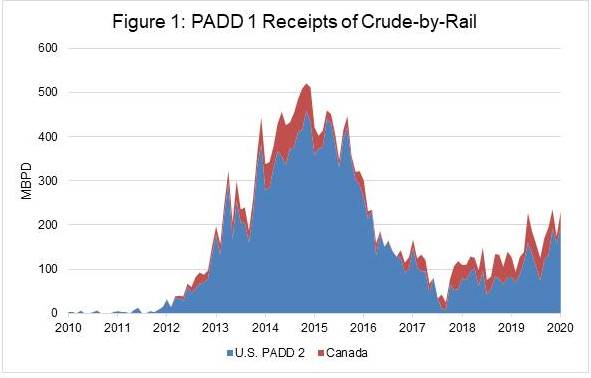

PADD 1 historically relied primarily on West African light and medium sweet crudes, with Eastern Canadian, Persian Gulf (primarily from Saudi Arabia), and Latin American barrels also making up a significant part of the regional crude slates. However, as West African production has stagnated since the mid-2000s (and, more recently, began to decline) and many regional light crude refiners have closed, East Coast refiners have been backing down on these barrels. Refiners that have continued to operate have replaced most of these light sweet West African barrels with Bakken crude railed from North Dakota. In fact, PADD 1 refining experienced somewhat of a renaissance from ~2013-2015 as the economics to process these railed barrels were very strong due to pipeline capacity constraints in North Dakota that drove wide regional crude differentials. However, because of declining regional production when crude prices fell in 2015 and the completion of DAPL in mid-2016, the economics to process Bakken in PADD 1 deteriorated. This dynamic was a key contributor to the initial PES bankruptcy in early 2018. As Bakken crude production began to outpace pipeline capacity again in 2018 and 2019, the economics for processing Bakken in PADD 1 improved (though not to the level seen in 2013-2015) and crude-by-rail volumes to PADD 1 increased in 2018 and 2019. Similarly, wide Canadian differentials have led to about 45 MBPD of Canadian crude-by-rail to PADD 1 since mid-2017. The ability to rail Canadian crude, however, is effectively limited by regional refinery configurations, which, with the exception of the two PBF plants, are geared primarily toward light sweet crude. Note that the United refinery in Warren, PA, has routinely imported ~60 MBPD of Canadian crude by pipeline. The remaining Canadian imports are made up of Eastern Canadian offshore production. Figure 1 shows historical crude-by-rail volumes to PADD 1 while Figure 2 shows total PADD 1 refinery crude inputs by source.

In the current environment, and continuing for the near future, PADD 1 refiners are being forced to make drastic throughput cuts due to cratering demand as shown by the declines to 450 MBPD. Longer term, the economics of railing Bakken crude to the East Coast are likely to deteriorate considerably as production there falls over the next couple of years due to low prices and DAPL expands with the addition of new pumping capacity. Similarly, the expected completion of the Enbridge Line 3 replacement project and a few smaller debottlenecks over the next 1-2 years combined with slower production growth will likely lead to deteriorating economics to import Canadian crude-by-rail. At the same time, increasing Saudi Arabian production (once the current OPEC+ cuts go away) will likely make Middle Eastern crude more attractive. For those with cokers (the two PBF plants), this is good news, as they will be able to take advantage of wider sweet-sour and heavy-light differentials without being forced to sell into the high sulfur fuel oil market. For the other regional refiners, however, a widening of these differentials is bad news. These refiners will likely be, once again, forced to turn to expensive West African barrels. As such, an additional refinery closure in the region remains a possibility, though the PES shutdown has certainly improved the prospects for the remaining regional refiners. Nonetheless, the Northeast demand outlook (even after the COVID-19 lockdowns go away) remains challenged, particularly with refined product supply available from the USGC, Europe, and, increasingly, PADD 2.

PADD 5

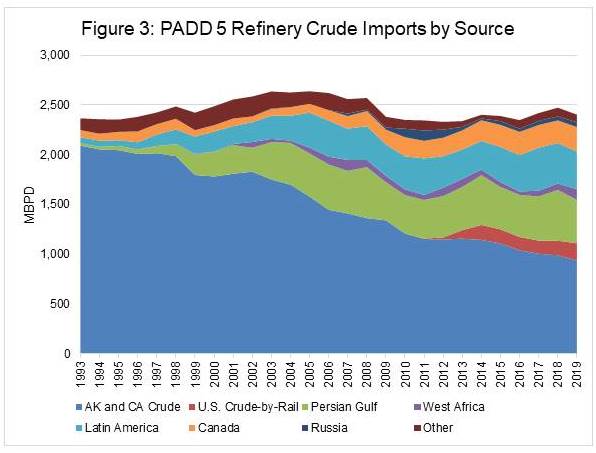

PADD 5 share some similarities with PADD 1, but is also different in many ways. PADD 5 can be divided into three distinct refining regions – Southern California, Northern California, and the Puget Sound. One refinery remains in each of Hawaii and Alaska as well. The Hawaii refinery (now owned by PAR Pacific) remains reliant on a combination of Alaskan and imported crude, while the Kenai, Alaska refinery (owned by Marathon) processes Alaska crude. Both are niche refineries that supply local markets. Figure 3 shows historical PADD 5 refinery crude inputs by source.

Most of the California refineries were designed to process local heavy crude production and increasing volumes of ANS crude in the late 1970s and 1980s due to the new production coming from Alaska. However, as combined local and Alaska production has fallen from a peak of almost 3 MMBPD in the mid-1980s to under 900 MBPD in 2019, California refiners have been forced to increasingly turn to imported barrels to fill their crude slates. The local California production from the San Joaquin Valley is unique and hard to replace. These crudes are generally heavy, high TAN, and high in aromatics, but relatively low in sulfur. As a result, many California refiners are sulfur limited and this can provide a challenge because of the limited availability of heavy sweet crude oils. Many California refiners have turned to various Latin American grades as the best replacement. Those that can handle higher sulfur content and have the logistical capability to handle larger vessels have increasing imports from the Persian Gulf. In fact, PADD 5 remains the most dependent of any U.S. refining region on Persian Gulf imports. Further, similar to PADD 1, the Jones Act prevents PADD 5 refiners from being able economically access U.S. LTO from the Gulf Coast and local opposition to rail has limited this option to the existing 150 to 200 MBPD capacity to the Puget Sound refineries from North Dakota.

Going forward, California crude production will continue to decline and regional product demand is likely to decline as well, forcing refiners to not only increase their reliance on imports to fill their refineries, but also on exports to move products. That is, unless another California refinery closes permanently. The completion of the Transmountain expansion, which now appears more likely, will provide a major boon to those refiners that can handle the high sulfur present in most Canadian heavy crudes. Until Transmountain is completed (or if it is never completed) California refiners will be forced to increase their dependence on Latin American and/or Persian Gulf Imports. The end result will depend largely on OPEC/Saudi strategy and pricing after the current OPEC+ agreement expires. If Saudi Arabia decides to pursue increased market share, the discounts offered on their crude are likely to lead to the increase primarily coming in the form of more Middle Eastern imports, and if Saudi Arabia backs away from this strategy, the incremental imports are likely to come primarily from Latin America.

The Pacific Northwest refineries historically processed primarily Alaskan North Slope (ANS) crude oil and smaller volumes of Canadian crude shipped through Transmountain. However, as Alaska production has declined, the refiners have been required to find new sources of crude, turning primarily to crude-by-rail from the Bakken, and, to a lesser extent, Canada. Still, Washington State law SB5579, passed in 2019, has effectively capped crude-by-rail volumes into the state at 2018 levels, so further growth in this area is unlikely unless the law is repealed or declared unconstitutional. The completion of the Transmountain expansion will obviously provide improved access to Canadian barrels, but until then new sources of crude will need to be found. The most likely sources for this crude will be Brazil, Russia, West Africa, and the Middle East.

In the short run, all PADD 5 refiners are being forced to reduce crude runs due to cratering demand, with total crude runs falling by about 700 MBPD in the past month (even before the upcoming Marathon Martinez shutdown). It’s possible another refinery (especially one which produces a high proportion of gasoline) could join the Martinez plant in coming down entirely. This would be more likely if the COVID lockdowns on the West Coast persist, a distinct possibility considering the very cautious attitudes in regards to “opening up” that the Democratic governors in the three West Coast states have exhibited. We expect that most of the reductions in crude runs will continue to come from imports, with inputs of regional crudes likely falling only to the extent that production declines. We do expect that as demand recovers, hopefully beginning by sometime in the second half of 2020 and into 2021, that crude inputs can return close to pre-COVID levels, with Martinez (and any other potential shutdown facilities) coming back on line as economics dictate. Longer term, the possibility of a permanent refinery closure in the region remains, as the West Coast is about “one refinery long,” as evidenced by clean product exports of ~250 MBPD. If a refinery were to close, it would help support regional refining margins, as the West Coast is somewhat isolated from other U.S. refining regions and alternate supply options are difficult.

In this rapidly changing and very uncertain environment, Turner, Mason & Company will be following developments related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the timing of lockdown loosening activities and other relevant market drivers. We will be analyzing how those developments impact crude prices, differentials, product demand, crude production, refinery utilizations and ultimately industry margins and prospects. Some high-level aspects of these analyses will continue to be presented and discussed in this blog over the next few weeks and months. We will be incorporating the analysis in a detailed and comprehensive way in the next edition of our C&RPO, scheduled to be issued in the summer. As always, the C&RPO will include a detailed forecast of both crude and refined product prices, product demand, refinery capacity changes, and a variety of other key industry parameters. For more details about this publication or other TM&C services, please visit our website or give us a call.